A circular economy is about conserving resources, with a positive environmental impact, made possible by renewable energy. This is not only desirable, it is economically necessary.

In recent years, the domain of sustainability and circularity has been increasingly claimed by the compliance world. With a few exceptions, laws and regulations – especially from Brussels – were the only reason for many companies to move. Often no more than the minimum necessary. This was followed by commercial motives (‘how can I stand out?’) and sometimes strategic interests, such as concerns about resource security in Europe. In reality, of course, this playing field has more nuance.

The introduction of the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) placed a heavy administrative burden on companies, leading to public resistance. That sentiment found its way into European politics and resulted in the so-called Omnibus package: postponing and watering down the CSRD. This removes the compliance reason for many companies to start working on sustainability and circularity. Business as usual?

That would be disastrous.

For beneath this resistance to bureaucracy lies a more fundamental motive for the Omnibus package: maintaining European competitiveness. Europe has become structurally too dependent on other continents – for materials, energy, production capacity, data, and even labour. This dependence is eroding our strategic autonomy. Europe lives on reserves – financially, materially, but also in terms of innovation and creativity.

Meanwhile, we are on the eve of two major investment programmes: one in response to the Draghi report, the other driven by geopolitical tensions and the war in Ukraine. Europe will have to regain its autonomy, and re-establish partnerships out of its own strength. And that will require a significant part of production and value creation to take place within the EU again.

That is exactly where the pain is: after all, one of the conditions for European investment programmes is “sourced and made in Europe”. Understandable and necessary. But this also raises the question: how do we guarantee our supply of raw materials?

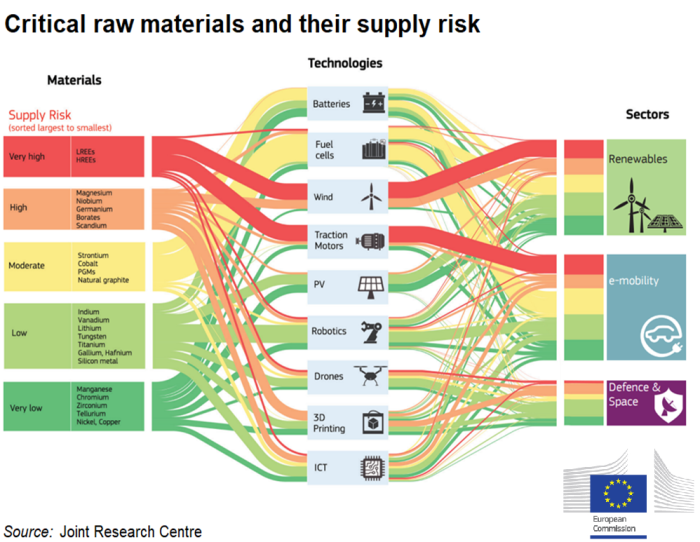

Europe’s dependence on raw material imports – depending on the type of material – is often between 60 and 90 per cent. A study published by Koese, Parzer, Sprecher and Kleijn in January this year paints a picture in which, even with the European Union’s self-sufficiency targets for critical raw materials, only for copper and lithium will we extract at least 50 per cent ourselves in the coming years. So for the rest, we will have to shop outside our continent’s borders. Even if raw materials are physically available, geopolitically they often are not (anymore). Feedstock security is therefore crucial for a successful reindustrialisation of Europe.

The urgency of a circular economy is therefore not (no longer) about compliance, but about economic and geopolitical necessity. The availability of materials should also come from within where possible – through recovery, reuse and smart (re)design.

That starts with passive recycling: making the best possible use of materials from discarded products. But that is not enough. We need to move towards active recycling: designing products with reuse, disassembly and material conservation in mind. Only then will we keep quality and value in the European supply cycle.

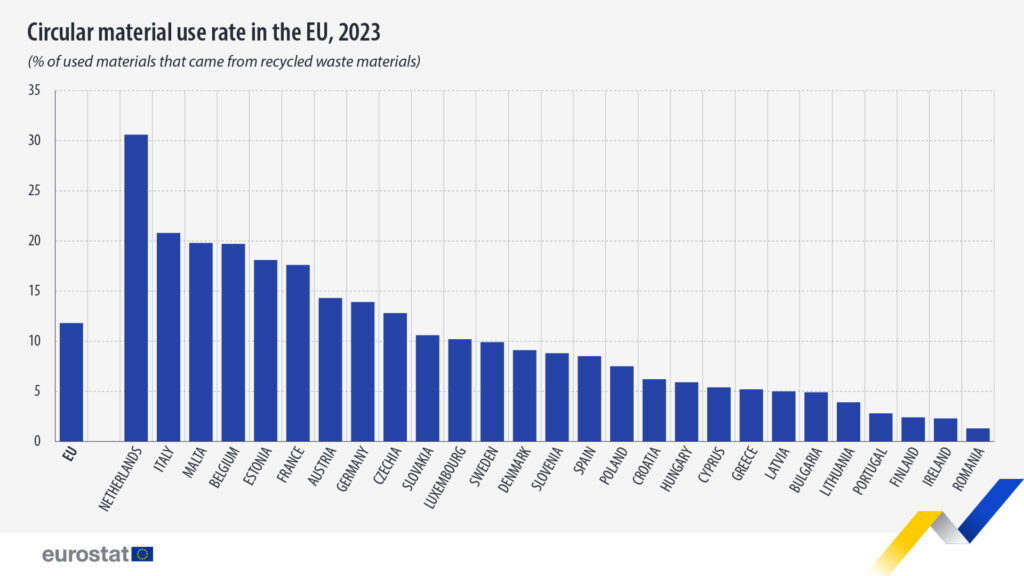

Can material recovery completely replace imports? No – certainly not in the short term. But the share of circular raw materials can and must rise substantially. For instance, in 2022 (these are unfortunately the most recent figures), 41% of plastic packaging was recycled in Europe, an increase of 10% in 10 years (Industry Intelligence, 2024). In the same year, we in Europe managed to recycle just over 70% of the paper we use, the target for 2030 is 76% (CEPI, 2024). Across the European Union as a whole, 11.8% of all materials used had a recycled origin in 2023 (Eurostat).

That share is still far below potential despite frantic efforts by recyclers, legislators and end-product manufacturers. The absence of economic necessity has hampered real innovation in recycling so far. Moreover, circular solutions are often judged on short-term impact, while the development of primary materials is funded and facilitated on a long-term basis.

It is therefore essential that we work towards a well-functioning material intelligence system, such as the dynamic digital product passport. This provides insight into composition, origin and processing of products – crucial for high-quality recovery. Fortunately, forerunners are already working on this and the European Commission, through the ESPR legislation, is embedding it more widely. But let’s avoid the trap of excessive bureaucracy: the goal is innovation and effectiveness, not tick boxes.

Europe needs to regain its strategic autonomy as soon as possible – and that requires a renewed, resilient industry. The knowledge and technology are there. What is needed now: the will and cooperation. And that requires a well-tuned mix of sectors: from mining to recycling, from agriculture to high-tech assembly.

As Pieter Hasekamp (FD, 29-3) and Ingrid Thijssen (31-3) recently pointed out, Europe’s future requires a holistic approach to industrial strategy. It is precisely the seemingly unattractive links – reverse logistics, dismantling, refurbishment, urban mining – that are crucial. Compare it to a Swiss watch: if one cog is missing, it stands still.

Let us finally see the circular economy for what it really is: not a moral imperative, but a historic opportunity. A lever for strategic autonomy, security, innovation and prosperity.